Art and the Politics of Pleasure

Art and the Politics of Pleasure

Carolina Azevedo

Chantal Akerman, Je Tu Il Elle (1974)

Coming of age as a woman can be one hell of a ride. Aside from the drastic body changes, hormonal issues, and mood swings, there is a specific issue most cishet men don’t have to worry about for a single day in their lives: sexual pleasure – along with sexualization and pretty much the whole idea of sexual relations.

As women and non-binary people, we grow up learning how to dress, sit, walk and talk in order to not be prey to sexual assault. While women have had the power to fight for their rights and have indeed gained space within societal and political spaces, male sexuality still very strongly overpowers female sexuality. As a consequence, growing up, we are not taught anything about sex, especially our own pleasure. It is still frowned upon when we talk about masturbating, a large number of women don’t even know what an orgasm feels like or how to achieve it, and heterosexual sex is still mostly about male pleasure.

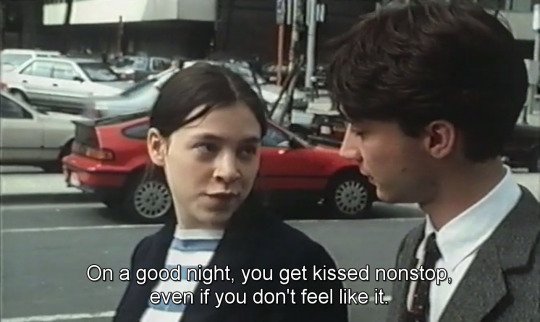

Chantal Akerman, Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (1994)

One of the pains of growing up as a woman or non-binary person and engaging in relationships with men comes from facing frustrations related to a lack of sexual pleasure. Due to heterosexual men being taught to centralize their own pleasure, the norm in sex is for men to simply use women as a means for personal climax.

Years of pornography consumption and inaccurate media representations of sex have resulted in cishet men learning from a young age that all they have to do is shove it in and get it done, with no regards to what their partner feels of wants – and even if they care about what we feel, they most likely don’t even think, or know, we have any wishes to fulfil during sexual relations. And the worst part is that it is extremely hard for women to actually talk about it shamelessly, and so many girls and gender non-conforming people on the verge of adulthood suffer silently not knowing whether they are the problem or not.

Despite the fight for sexual liberation, female pleasure is still taboo within western society, but some women have had the guts to speak up about it using different mediums as an amplifier for the female sexual experience. Singer PJ Harvey talks about sexual frustration and the pains of being with a man at a young age in her first two albums, Dry and Rid of Me.

Kevin Westenberg, PJ Harvey Walking (1995)

Tracks such as Dry and Rub ‘til it Bleeds disclose the fact that her male partner has no ability whatsoever to make her excited, he simply does not know how to do it or doesn’t even bother to do so. With no regards to societal conventions and musical critique, Harvey sings

“you put right in my face / you leave me dry / you leave me dry”,

unapologetically saying what a great deal of women wanted to say, especially in 1993.

The albums tackle numerous issues surrounding being around men and feeling silenced by patriarchy. In Man-Size, Harvey says: “Man-sized no need to shout / Can you hear, can you hear me now / I’m Man-size” whilst challenging exactly the gender standards she criticizes. Or Sheela-Na-Gig, in which she references Sheela-na-gig statues, ancient carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. Throughout its lyrics, Harvey criticizes “imperious male demands” as she sings “better wash that man right out of my hair”.

Women filmmakers and writers have also had the strength needed to stand up in front of men and say what they wish about pleasure and sexuality as young women. One good example lies within Chantal Akerman’s filmworks, especially Je Tu Il Elle and Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles. In both movies, Akerman makes a subtle yet strong commentary on the way women are perceived by the media – especially during sex scenes – and the pains of maturing sexually.

In Je Tu Il Elle, the director takes a stand on what female pleasure actually looks like. Without casting plastic-looking women with unrealistic bodies and views that appeal only to men, Akerman films a sex scene in which two women come together in unison to pleasure themselves. Whilst in Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles, Akerman tells the tale of a high schooler coming to terms with her sexuality as she gets to know other boys and girls her own age.

Chantal Akerman, Je Tu Il Elle (1974)

The experiences of white women, such as PJ Harvey and Chantal Akerman, however, correspond to a small fraction of the experience of coming of age as a woman in western society. One of the many women who have fought for the recognition of pleasure as a black person, who speaks up a lot about the queer experience through the arts, has been Janet Jackson.

Sexuality has always played a big part within Jackson’s career, as she herself says: “For me, sex has become a celebration, a joyful part of the creative process.” Through her song writing, Jackson has expressed many times how she feels as a black woman who has gone through the process of coming to terms with her independence and pleasure. In Control, which might be one of her stronger songs lyric-wise, she tells “a story about control, my control,” and just how she felt finally taking charge of her life, career, and relationships as a black woman in a world and business ruled by white cishet men.

Janet Jackson, Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 album cover shoot, 1989 © Guzman

Janet Jackson, Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 album cover shoot, 1989 © Guzman