Ctrl + Alt + Delete: Digital Communities in Cancel Culture

Ctrl + Alt + Delete: Digital Communities in Cancel Culture

Megan Matthews

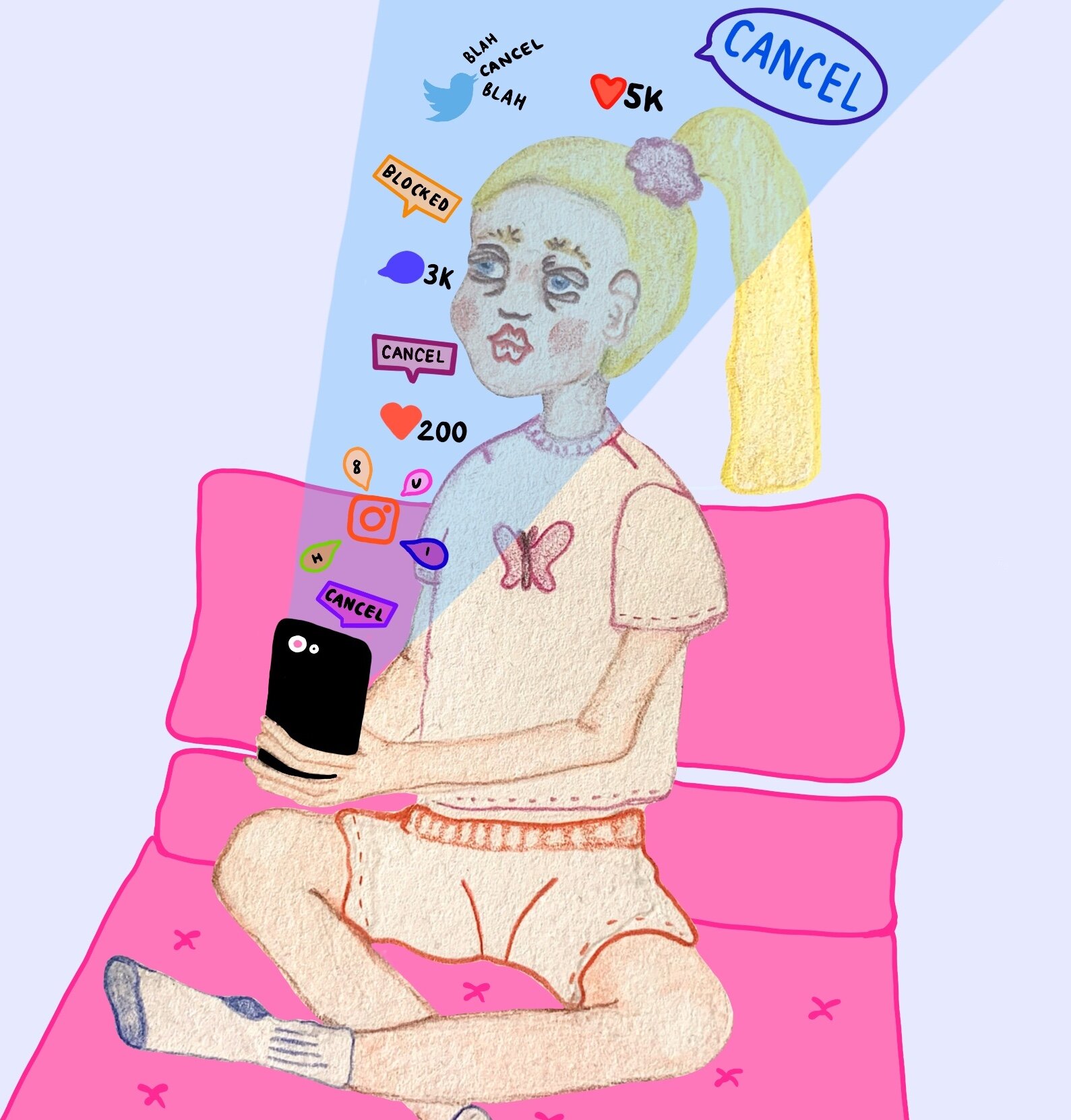

Artwork Anna Morrissey

Ctrl + Alt + Delete: Digital Communities in Cancel Culture

Megan Matthews

Artwork Anna Morrissey